This is the first post for the FreeNampeyo blog.

How In Search of Nampeyo came to be written

Steve Elmore is an Indian Trader and owner of Steve Elmore Indian Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He has been studying Hopi pottery for over twenty years and works closely with contemporary Hopi potters. Events were set in motion when Steven LeBlanc, then Director of Collections at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University asked Mr. Elmore to write a book for the Peabody Museum Press on his discovery that many of the ceramics in their Keam collection were the work of the great Hopi potter Nampeyo, and not a random assortment of pottery made by hundreds of different potters, as previously thought.

Steve wrote the book and submitted it, eventually receiving three reviews, which he was asked to respond to. He was then asked by the press to do a major revision of the book for the more scholarly “Papers” series, rather than the “Collections” series he had originally written for. Six months later, he submitted this second version. The manuscript was rejected. A Formal Notification letter from the board returned to him “all rights” in all versions of the manuscript. The letter recommended that he publish elsewhere and made some suggestions as to other publishing venues.

Relying on this letter, and double checking with several intellectual property attorneys, Steve decided to self publish the book, as it had already been through many reviews and was essentially finished. He published In Search of Nampeyo: The Early Years 1875 - 1892 in 2015. In Search of Nampeyo has won four national book awards, including awards for best art book and best interior design. It has received many positive reviews.

However, Harvard was displeased and sued him for breach of contract, copyright infringement, and false designation. Steve countersued on a number of charges including bad faith, interference with business, and conspiracy to steal intellectual property. Right now, the book is under a temporary injunction as Harvard has persuaded a judge that the book has caused them “irreparable harm”.

Harvard's Copyright Infringement Claims

The rest of this post will look into the copyright issues that are raised by Harvard's lawsuit. I will give the context and try to summarize the main issues.

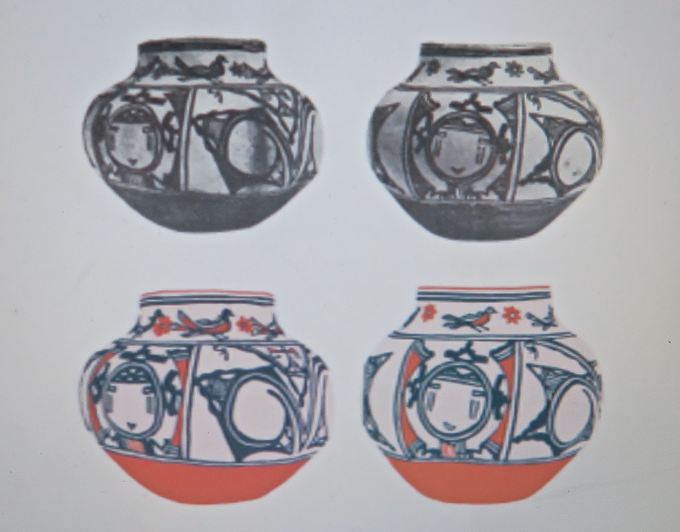

The Keam collection was purchased by Mary Hemenway in 1892 and after she died, donated to Harvard in 1894. It was unpacked about 85 years later, and In 1980 Harvard published a book called Historic Hopi Ceramics (HHC) containing simple black and white photographs of the ceramics; it is a catalog of the collection. In the manuscript that Steve submitted to Harvard were some photos cut from HHC which he intended as place holders for future photography. After the manuscript was rejected, he hired a designer to do three color, hand drawn, illustrations of the designs on these pieces of pottery and included these in his book. These illustrations are the subject of Harvard's copyright infringement suit. Harvard did not make any of the pottery and all these pieces of pottery were made before 1892 when the collection was purchased, so all would be considered in the public domain. Harvard's argument is that since they photographed the pottery, no one can make copies of the designs depicted in their photographs.

In Hopi culture, designs are passed down in families. Nampeyo taught her daughters to make pots and passed her designs to them and these designs have now been passed down and are in use by the fourth and fifth generations. Nampeyo family potters consider the designs to belong to them and/or to their culture. Despite Harvard's statements to the contrary, if the court rules in their favor, Harvard would in fact own not just the copyright to their photographs, but to the designs themselves.

Steve did not use their photographs, nor did he make exact copies of their photographs. The illustrations leave out all details of the pottery itself such as shadows, chips, cracks, uneven paint and slip, and fire clouds. They also idealize the design, adding elements not visible in the photographs. It is the designs that are the subject of the text and shown in the illustrations. While it is true that the designer did use the photographs from HHC to create his designs, he also used additional sources in order to see the details of the designs and colors.

Harvard claims that its catalog shots have sufficient creativity to be copyrighted as original works in their own right. In particular, Harvard points to the choice of angle as original, because other angles could have been chosen. Here is Harvard's strongest example. They invoke the "reasonable person" standard. The illustration should be considered a violation of their copyright if a reasonable person, without specifically searching for differences, would regard the two images as identical.

The big question here is where a line is to be drawn. A clear case would be one in which a photographer used a Hopi pot as part of a photograph meant to be a piece of art in its own right. If this photographer put the Hopi pot on white velvet, lit it with purple light, and surrounded it with apples, no one else could use the same set-up and take that same image without violating this photographer's copyright as the creative elements of background, lighting, and setting were clearly chosen as artistic decisions. However, the fact that a Hopi pot was included in the photograph certainly does not give the photographer ownership of the design on that pot. Court decisions have often relied on the technique of first filtering out public domain portions of the photograph, and judging copyright claims on the basis of the remaining elements. On the other end of the spectrum is a verbatim copy. If Harvard's own photograph was simply reproduced in Steve's book, this might be considered a copyright violation.

I say might be considered a copyright violation because the issue of fair use must be considered. Since Mr. Elmore picked out a small number of pots from the entire Keam collection to use in a scholarly argument establishing Nampeyo as the artist who made these pots, the use he made of HHC should be considered transformative of the original work and serving the purpose that the fair use doctrine was established for, furthering the development and presentation of new knowledge. He did not use the "heart" of HHC, which is simply a catalog and he did not decrease the value of the original book. In fact HHC has increased in value since Steve published In Search of Nampeyo.

I have now read rather broadly on the subjects of copyright and fair use. I do not think that Harvard has a legitimate case against In Search of Nampeyo, and I certainly don't think that Harvard has any right to Native American designs. Those with the desire to read the pleadings will see that the lawyers for the two sides have very different approaches to the presentation of evidence and that the rhetorical strategies are especially different. These differences, to my relatively inexperienced eye, often seem to influence a judge's rulings, seemingly looming larger than the law and the facts of the case.

The contract case is related, but separate. Since the images were in the manuscript that Harvard returned to Steve with "all rights", the letter appears to have granted him the right to reproduce Harvard's photographs if he chose.

If you want to read the court documents associated with the copyright, they are linked below. Steve's lawyers filed a Motion For partial Summary Judgement, asking the judge to review the facts and the law and rule on just this aspect of the case. Harvard's lawyer filed a response and also his own motion for a summary judgement for another photograph, and then Steve's lawyer filed a reply to the response and a reply in opposition to Harvard's new charge.

And, for fun, a song imagining what would happen if Steve Elmore really did have to power to cause "irreparable harm" to Harvard: Dude, Where's Harvard